The board meetings for Cloverlay — a group of Philadelphia businessmen who financially backed heavyweight Joe Frazier in the 1960s — were often running late and causing the members to return home after dinner. Their wives, they told Joe Hand, were complaining. Perhaps they could meet earlier, they suggested.

“They said, ‘How about we do this, Joe? Why don’t we make it for brunch?’” said Hand’s son, Joe Hand Jr. “My dad said, ‘No problem.’”

Hand, who died Thursday at 87, was a Philadelphia police officer assigned to the subway when he read a story about Cloverlay in the Daily News. The group formed to support Frazier, who was broke after winning a gold medal at the 1964 Olympics with a broken thumb.

The businessmen paid Frazier a salary, gave him an apartment, paid his trainer, and built him a gym on North Broad Street in exchange for a cut of Frazier’s earnings in the ring. The businessmen acted as Frazier’s manager and sold shares of Cloverlay for $250, which would rise in value if Frazier won the way they believed he could.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/CNLSWEK5H5EMNPPAW73JPPF2LA.jpg)

Hand wrote a letter, asked to get in, and took a loan from Police and Fire Federal Credit Union to pay for his share. The cop quickly rose up the ranks of Cloverlay by agreeing to be the office manager, which earned him an extra $200 a month when he wasn’t on patrol.

Hand became close with Frazier, gleaned business advice from an investor group that included Philadelphia dignitaries W. Thacher Longstreth and John B. Kelly, counted the attendance at Frazier’s fights, and adjusted the starting time for those board meetings.

“He gets back in his car and drives back to his office,” Hand’s son said. “He says to his secretary, ‘I need to talk to you for a second.’ She says, ‘What’s the matter, Joe?’ He goes, ‘What is brunch?’”

The cop in Cloverlay

Joe Hand lived on Jackson Street in Wissinoming when he wrote his letter to F. Bruce Baldwin, the president of Abbotts Dairy and the chairman of Cloverlay.

“Doctor Baldwin got back in touch with my dad and said, ‘We’re from the same area. I think we even live on the same street,’” Hand Jr. said. “He said, ‘I live on Jackson Street.’ We were living in Northeast Philly on Jackson Street in an 18-foot-wide rowhome, and Doctor Baldwin lived on Jackson Street miles away from us on this big piece of property. My dad, being true to who he is, said, ‘Yeah. We must be neighbors.’ That’s great.”

And that’s how a street cop making $7,500 a year found himself at the next Cloverlay meeting with some of Philadelphia’s movers and shakers. Hand borrowed his money, bought a share, and was in.

“My dad had no idea about boxing,” Hand said. “He didn’t know anything about the sport. He just loved the story. He said, ‘I knew something good would come out of it because it’s like your mom says, you are who the company you keep.’ He said, ‘I was just hanging around with these really smart, successful guys.’”

Frazier scored a first-round KO in his first fight under Cloverlay and broke his opponent’s jaw with his signature left hook in his third fight with the investors. Cloverlay, feeling bad for Frazier’s battered opponent, gave the fighter $250 while he was recovering at Hahnemann University Hospital.

Two years later, Frazier became heavyweight champion by knocking out Buster Mathis, who beat Frazier years earlier in the Olympic trials but had to give Frazier his spot on the 1964 team after being injured. For Cloverlay, it was proof that they were backing the right guy.

And the return on their investment came three years later when Frazier was paid $2.5 million after beating Muhammad Ali in 1971′s “The Fight of the Century.” The cop said his investment grew to $300,000 when Cloverlay disbanded in 1973 after Frazier retired for the first time.

“My dad was always a real risk taker,” Hand said. “There was never a 9-5 job with him. He worked all the time. He hustled, and he loved the fact that he was in this Cloverlay thing. And he did make money with his shares because he was an early investor.”

» READ MORE: Family members recall Joe Frazier’s ‘Fight of the Century’ victory over Muhammad Ali

Pioneer of closed-circuit

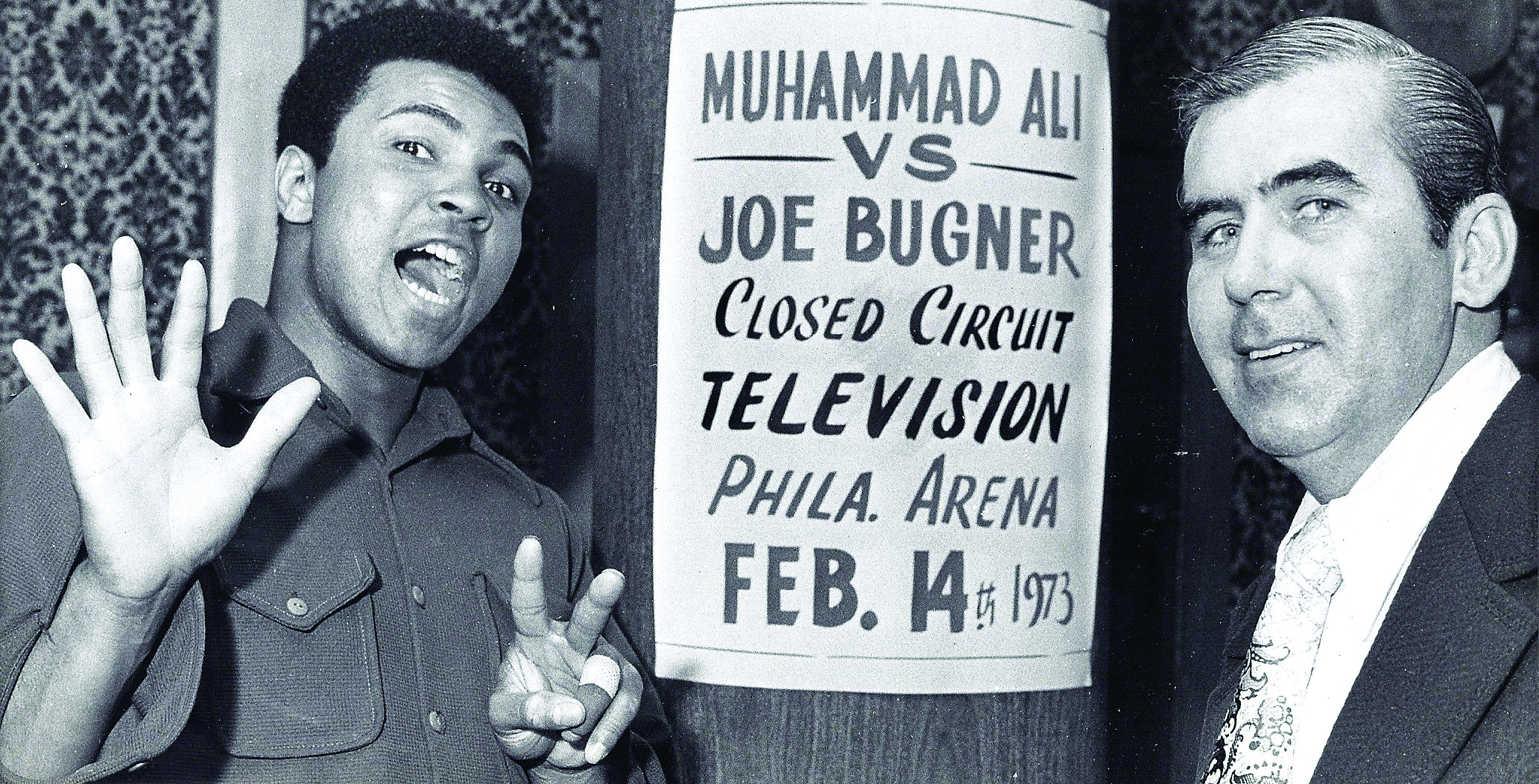

First, the businessmen gave Hand the challenge of finding out what time brunch started. Next, they asked him to figure out what “closed-circuit TV” was all about.

“He said, ‘I’ll find out and I’ll come back to the next meeting and let you know,’” Hand said. “He went to the library, looked it up, came back, and said ‘Look, this is how I think this could work.’”

Hand told the investors that they could bring movie screens into arenas across the country and sell tickets to watch live telecasts of Frazier’s fights. The first few closed-circuits were knockouts. Hand, still a police officer, then started his own company: Joe Hand Promotions.

It was pay-per-view before pay-per-view as fans paid to view telecasts of fights at arenas like the Spectrum, Radio City Music Hall, and Pittsburgh’s Civic Arena. Hand ran it all from Jackson Street.

“My Aunt Pat, my dad’s sister, ran the business for him during the day,” Hand said. “Then my dad would come off of work as a cop and run the business in the basement in the house. We eventually moved to Somerton, but we weren’t there that long. My mom kicked us out of the house. She said ‘I’m not waking up every morning and having my coffee with the Fed-Ex delivery guy. This thing is getting out of control.’ The business was growing, and our landlord, my mom, booted us.”

Hand’s closed-circuit business was already taking off by the time Cloverlay disbanded. In 1976, Hand retired from the police department after suffering a heart attack. He then focused solely on the closed-circuit business, and Joe Hand Promotions soon became the leader of “out-of-home live sports content.”

If a bar or restaurant wanted to air a fight, they had to pay Hand. The business now has the rights to everything from WrestleMania to German soccer games.

Booted from Somerton, Joe Hand Promotions is now headquartered in a 25,000-square-foot office building in Feasterville. More than 50 years later, Hand’s business is strong. And it all started with a cop who had to figure out what “brunch” meant.

“My dad used to always say, ‘When the Cloverlay guys said, ‘Hey we could really use some help doing something, he said, ‘Joe, I raised my hand every time. Sometimes they said, ‘OK, Joe. Here’s the assignment.’ And I would say, ‘How the hell am I going to figure this out?’ But I needed the money, I always wanted to say yes, and I always wanted to be a team player. Every time, I got the assignment, somehow and someway, I figured out a way to pull it off,’” Hand’s son said.